To lie in a tent listening to the soft murmuring of campsite neighbours is to hold summer in your palm. Outside our thin, coloured home weka ran laps, ducks tucked in, the tide rolled closer, and people slept in their bright cocoons. My friends lay next to me, their breathing evening out and my mind slowly drifting with the fading calls of tūī, pīwakawaka, and kererū.

I’m not sure when I forgot I was a teacher, but at some stage I did. These last six, beautiful weeks afforded me a break — a proper one. I have had a true kiwi summer, and I hope this small glimpse relaxes you and lets you in on the adventure too.

I didn’t mean to forget I was a teacher it just happened one day. Maybe the day the tūī said, Kate, Kate go for a walk in the bush; or the day the ocean whispered, come for a swim it’s nice. I slipped into the glassy water, the sun skimming the surface and I stroked forward beneath the sky out to where I couldn’t touch, closer to the horizon than the shore. Black-backed gulls tilted towards the sea, the tips of their feathers glancing off the water around me; starlings — a murmuration of them — ballooned overhead, their motley cloud thinning each time the group dove towards their island for roosting. The black sand sifted between droplets. West coast sand is proper stuff that burns your feet and darkens the water. It falls from your togs in the shower, pooling at your feet, each time you are left wondering whether you removed half the beach without knowing. I hang my togs from my bedroom window to dry, knowing they won’t be there long, soon put back on — slightly salt-crusted and ready for another swim.

Days were long, the sun up before I was, and still up when I tucked in. More often than not, I would lie with my blind and window open watching the pink of the sun stroke the Pouakai Ranges on its way down to the horizon. In those long hours — gratefully so — I kayaked and swam, I walked and ran, I climbed mountains and snorkelled oceans. I talked and listened; I moved and was still. In my red kayak with a yellow life jacket I paddled where I wanted, stopping to watch yachts under sail cut through the water. Some days I walked in the bush, stilling my eager legs to allow my eager eyes and ears to soak up the vast canopy and bird song. The distinct click clack of tūī song seeping into my veins again.

I explored like a child; led by whim. A walk? Ok. A run? Ok. A climb to the top of New Zealand’s deadliest mountain? Ok. (That last one, you do need to know what you’re doing). I snorkeled again and again, happy to be back floating amongst unfazed fish, staring at each other and going on our way. We’re the aliens. They’re welcoming for the most part.

I went from the East to the West coast of the North Island, down to the North coast of the South Island. The night we arrived to the Coromandel, we were greeted by a customary summer thunderstorm. Thrashing rain, bone-rattling thunder, and streaks of lightning screamed and yelled for all of 20 minutes. Then summer began. The white sands of Hahei blind eyes rather than burn feet like the black sands of home. On that first evening — the one with the rain — I peered put at the neat vege garden, knowing the courgettes and beans picked fresh would be brought straight to the table each night. My grandparents, mum, dad, and I read and played scrabble waiting out the rain. As

knows, a bach isn’t complete without an array of jigsaw puzzles, games and faded books. 37 years worth of family art graces the walls. The bach was a two-bedroom affair when it was first bought by my great aunt and uncle all those years ago. Now it has four bedrooms and a second story, but it still retains lovely nods to the original bones — but now it has a great kitchen and a nice warm shower. It’s an ongoing project — the walls are going to be repainted soon, and the light fittings have just been replaced. The neighbours lent my sister and I kayaks to go exploring on. So we did. We paddled around to Cathedral Cove as we have done so many times before, but each time I see something new, or think a new thought. I grow through the years as do the face of the cliffs. Changing slowly with the influence of the ocean, tides, skies, and people. There is a comfort in returning to the same place again and again. Knowing Hahei will always be there, the same pohutukawa tree holding the rope swing by the cliffs with names etched into it. L + K 4Eva.

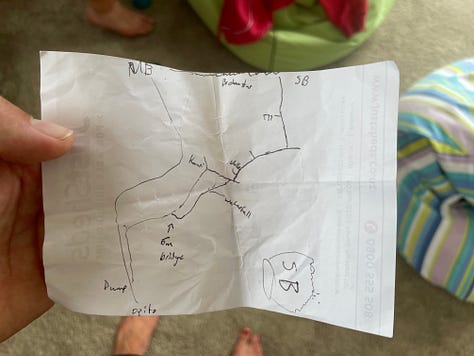

I ducked an hour over the hill to visit a friend at his family’s bach for three nights. We snorkelled and walked, navigating solely with a hand drawn map. Cross the bridge on the right, but only once you’ve gone past one turn-off already, then follow the scallop and paua shells nailed to the trees, once up the hill, drop down into a valley and continue walking until you reach the bay. On the way back, go around the rocks at low tide until you reach a set of broken stairs, go up there… We got there, and back. We ate the fresh, venturing shoots of supplejack as we went — feeling capable knowing what we could eat from the bush. We said hello to every person, stopping often to share stories. My friend knows almost everyone in that bay it seems. And almost everyone knows him. That’s summer. A return to small places, knowing neighbours, and offering a hand.

I ventured down to my Grandad’s small farm with my family not long after Hahei. The vast paddocks and faint baaing of sheep, a contrast to the bush, birds and ocean I had gotten used to. It rained each morning and we played golf or helped out around the place each afternoon. I explored shelves of old books and lay about reading my cousins’ palms from a 1927 guide on how to do it. I walked often — sometimes around the paddocks, sometimes around the streets of the small town he lives on the edge of. Dry grass chattered between fence lines. The clack of scrabble tiles made its way from windows. The shifting gravel from a passing stock truck rose up then faded. This is summer, I thought to myself as I sipped a gin and tonic.

Then came the camping; a couple of nights in the Abel Tasman. We walked with packs loaded up — the night prior spent discerning what was a creature comfort and what was necessity. Snorkel - necessity. Soap - creature comfort. The gold sand caught and reflected sunlight back up through the ocean, demanding our attention with its glittering turquoise. We walked 13km on the first day, stopping to each lunch by a bubbling stream, rock hopping up and down. That night, we set up tents at a DoC (Department of Conservation) campsite my friend had pre-organised. A small whiteboard described the weather, the warnings (weka!) and whatever else. I think this summer is a hand drawn one — maybe all kiwi summers are. Slapdash, not too neat, freedom the undercurrent; I think. We slept well after a meal cooked on our camp stove; lying on thin sleeping rolls listening to birds and the ocean. Both a great comfort. Natural white noise. Two of us walked the next day while the other two read. We packed a day bag with towels, togs, snacks and water. We wore raincoats as at some point in the night it had started raining and wasn’t meant to let up for the day. It didn’t matter. Maybe mum is right in saying, ‘there is no such thing as bad weather, just inappropriate clothing.’ My mental list of birds seen on the trip grew as we walked. Kingfisher, heron, bellbird, oystercatcher. Feet splashed happily through puddles — really it’s easy to return to girlhood, sometimes I think I never left it. Lingering girlhood I like to say. I hope it sticks around. We reached Cleopatra Pools and changed in the open, bodies on display for Papatūānuku (Earth Mother) to see, no one else. Once our togs were on, we eased into the clear water. Mist hung at the tops of the hills as we swam in the valley. A natural rockslide wound its way from one pool to the next. We had the place to ourselves and for a while we lay still in the water, silent but listening and watching. I felt I may have visited Eden. Everything else fell away. What overtook me was a calmness and a clarity, I must seek this more often. This is living. Nothing else matters other than keeping my ear to Papatūānuku’s beating chest.

The walk out from our campsite two nights later was clear. The sun shone, we stopped to swim and snorkel, ducking down to come eye to eye with fish again. Our weary legs were glad to reach the car, and soon enough, wood fired pizza. Just what we needed. Other trampers we kept bumping into were at the DoC campsite, the pizza place, then the airport. There are two degrees of separation in New Zealand — maybe sometimes one. My cheeks were browning as they always do in summer, freckles becoming more pronounced, hair lightening slightly, tan lines making themselves known — jandals, togs.

I said goodbye, see you soon, to my friends at the airport. They were driving to visit me at home in Taranaki in two days. I got a text later, ‘we’re eating noodles from the camp stove, drinking a cider in a car park while we wait for a peanut butter factory tour.’ I laughed. Summer.

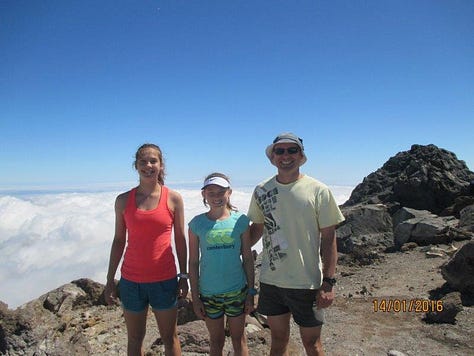

I got home and we sat outside as a family eating dinner. I popped inside briefly to get my hat and came out barely 30 seconds later to find my dad and sister asking, ‘want to climb Mt Taranaki with us tomorrow?’ Ok, I said, and that was that. (Bear in mind, we have done this climb many times before, if it’s your first, don’t take it lightly — plan, train, get advice.)

We packed bags and set alarms, we lay out gear — boots, gaiters, etc.

It’s tradition in our family, that once you have climbed the mountain, on your way home you must stop at the Egmont Village petrol station to get an ice cream. Once we took a hitchhiker from the mountain back into New Plymouth but warned him we would be making a compulsory ice cream pit stop. To which he laughed and said, ‘excellent, my treat.’

The climb is hard but you’re in good company, chatting to people as you walk in step — I met a man from Inglewood just down the road, and a man from Ireland (not just down the road). There’s an unspoken responsibility locals proudly but quietly bear, to keep an eye out for others. We asked how tired-looking people were faring, making sure they were keeping good time and knew what to expect.

At the summit a white silence met us. Devoid of wind in trees, birds, car noise, and chatter — the summit becomes a vacuum. Just the sound of my own sandwich chewing in my ears. We took compulsory photos. It was my 5th time up. Maybe I’ll aim for 50 times before I can no longer do it. Who knows. Anyway, the way down is fun. Skittering deftly like cats, we skated down the scree. I like the way the summit route is divided — bush track, the puffer (very steep part!), rock hopping, stairs (479 of them), scree, lizard (hardened lava), crater to peak. I have a mental map and I can see myself progressing along it as I go. Some advice I got when I first climbed it as a ten year old was, ‘the top is only halfway, you still have to go down.’ The top is joyful and so is the bottom. Got to love a good ice cream.

My friends arrived to Taranaki late the next day to a fading sky. Warmth still lingered, so we sat outside to eat the dinner my younger sister had made. We couldn’t believe what we could pack into a holiday. And we still had a week to go. In just three days we managed to climb Paritutu rock, go to two beaches, play tennis, visit a light festival, go to an op-shop, read, walk, go to a garden, and relax (of course). Three days of blistering sun. At the beach people ran like cats on a hot tin roof — black sand is hot, have I mentioned? So my friends lay for a while in the shade of the Taranaki Surf building. They said New Plymouth is a friendly place, everyone walking past said hi while they lay there. I was proud, I am proud. I like saying I come from New Plymouth, Taranaki. Living out on a limb in a place you can’t pass through but must make an effort to go to, means people who like a certain level of isolation live there. They (we) are a friendly bunch, you know every few people on the street, the place is slow (in a blissful nowhere-to-be way), people wear jandals (or bare feet), and people smile (a lot). The ocean is just there reminding you to go with the flow, the bush houses birds to sing to you, the mountain is an anchor steadying you. Though I know humans are not the centre, sometimes nature — particularly that in Taranaki — makes you feel that way.

We visited gardens with a single tennis court and a river at the bottom - and we were only one of two cars there, having almost the entire place to ourselves. The light festival provided art and thought, transporting us to another world while remaining in the cosy arms of native bush. Paritutu rock gave us perspective; able to survey the sea, mountain, and town we picked spots to visit. First Ngāmotu beach, then Fitzroy. I have written about home before, so I direct you towards that here. But just pick your happiest, most free, at peace summer memory — that’s Taranaki for you. Wild bliss.

I’m back in Christchurch now on the brink of a new year of teaching feeling content and refreshed, but slightly apprehensive. I love routine but I love adventure. I’ll hold this summer in the palm of my hand, maybe sleep with the windows open for a while yet, and go barefoot just a bit longer than I should. It’s been lovely, though that word hardly holds enough meaning. It’s been freeing. I am grateful.

Wow it sounds absolutely perfect! Such lovely photos. Love the idea of lingering girlhood.

Just what summers are made for!

Lovely, especially the photos. G’day from across the ditch.